As of Tuesday, January 20, 2026, scientific understanding of human physiology continues to reveal just how complex our daily survival truly is. We often take our body temperature for granted, assuming 98.6°F (37°C) is a static baseline. In reality, maintaining this internal climate is a high-stakes energy negotiation that never stops. Your body is essentially a furnace and a cooling system wrapped in skin, constantly adjusting to the chaos of the external environment.

Whether you are stepping out into a winter chill or enduring a summer heatwave, a sophisticated network of sensors and signals is working furiously beneath the surface to keep your vital organs functioning. This process, known as thermoregulation, is the topic of our latest deep dive.

Listen to the episode

Dive deeper into the science of how your body manages heat in this episode of The Workings of Our Bodies.

Listen to Thermoregulation: The Body's Internal Climate Control

The Hypothalamus: A Precision Thermostat

The story of thermoregulation begins deep within the brain, in an almond-sized structure known as the hypothalamus. Acting as the body’s command center, it receives a constant stream of data from thermoreceptors located in the skin and from the blood flowing directly through the brain.

This system is incredibly sensitive. Research indicates that the preoptic area (POA) of the hypothalamus can detect a deviation of just half a degree in core temperature.[1] When this shift is detected, the hypothalamus triggers a "red alert," mobilizing physiological resources to either conserve heat or shed it rapidly.

Cooling Down: The rRadiator System

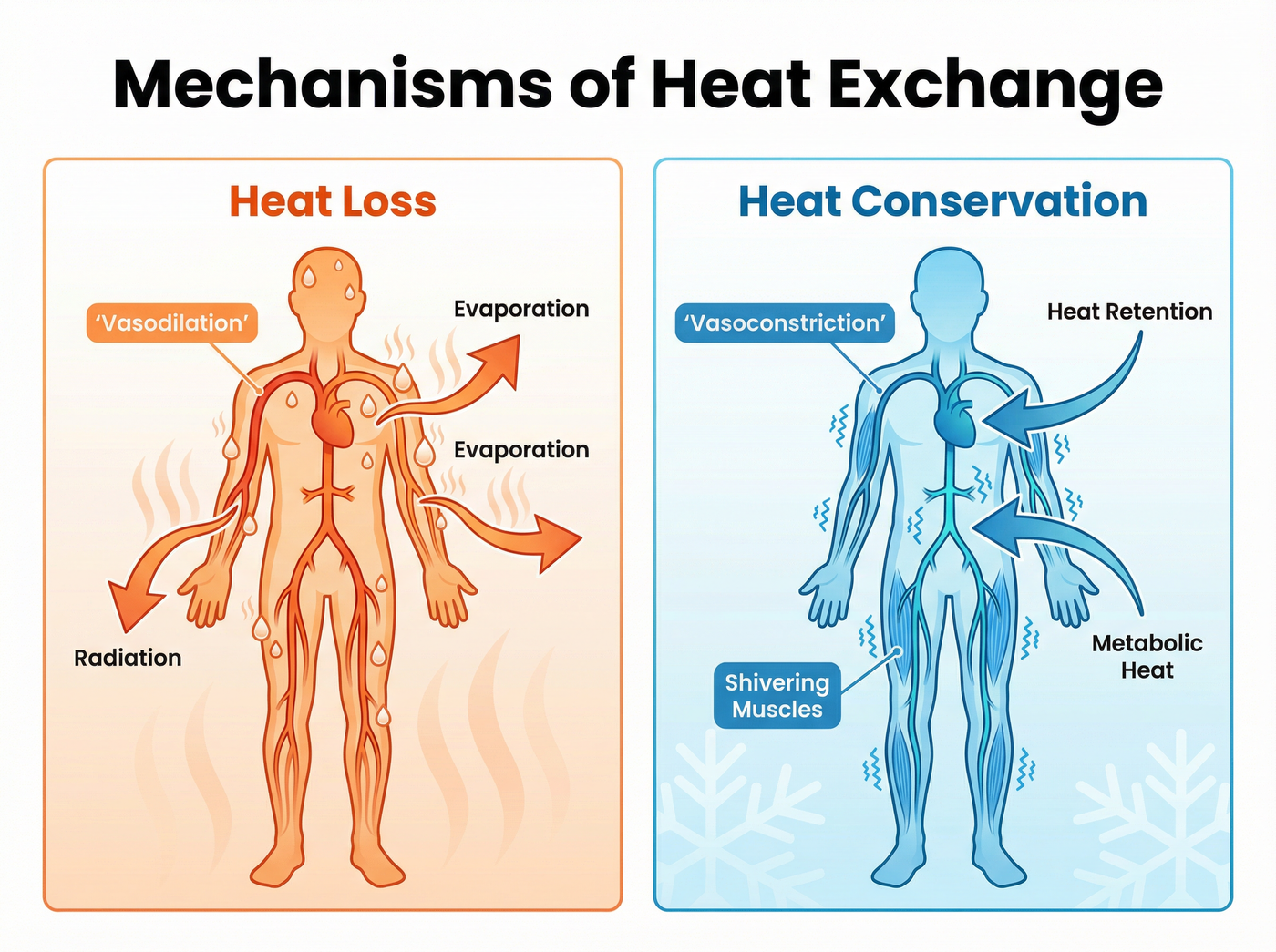

When the body overheats, the hypothalamus initiates a process called vasodilation. This relaxes the smooth muscles of blood vessels near the skin's surface, functioning much like a car's radiator. Warm blood from the core is shunted to the periphery, where heat can be released into the cooler air.

The volume of blood involved in this process is staggering. During intense physical activity or exposure to extreme heat, the body can direct between six and eight liters of blood per minute to the skin solely for heat exchange.[3] This creates a significant demand on the cardiovascular system, as the heart must pump harder to maintain blood pressure while so much fluid is diverted to the surface.

The Survival Dilemma: Hydration vs. Temperature

While radiation is effective, it relies on the air being cooler than the skin. When the outside temperature soars, the body must rely on evaporation—sweating—to cool down. However, sweating is energetically expensive and relies heavily on the body's fluid reserves. This creates a critical interdependence between temperature regulation and fluid balance.

In scenarios of severe dehydration, the brain faces a brutal choice: continue sweating to lower body temperature, which risks a fatal drop in blood volume and pressure, or stop sweating to preserve the circulatory system. Studies suggest that in these extreme moments, the hypothalamus prioritizes fluid balance and blood pressure.[1] The body will effectively "shut off" sweating to prevent cardiovascular collapse, allowing the core temperature to rise to dangerous levels—a calculated risk for survival.

Generating Heat: More Than Just Shivering

On the other end of the spectrum, when the body needs to warm up, it engages in vasoconstriction. Blood vessels in the extremities tighten, pulling warm blood back toward the vital organs. This is why fingers and toes are the first to feel cold; the body is deciding that the heart and brain are more important than the digits.

If conserving heat isn't enough, the body generates it. We represent this most commonly through shivering, which generates heat as a metabolic byproduct of muscle contraction. However, mammals also possess a mechanism known as non-shivering thermogenesis, primarily occurring in Brown Adipose Tissue (BAT), or "brown fat."

Unlike regular fat that stores energy, brown fat is packed with mitochondria and exists to burn calories for heat. The sympathetic nervous system triggers this tissue to produce heat rapidly without the fatigue associated with shivering.[5]

The Metabolic Cost of Stability

Maintaining a constant body temperature is a "tax" we pay for being endotherms. This cost is heavily influenced by body size. Smaller mammals, which have a large surface area relative to their volume, lose heat rapidly and must consume vast amounts of food to keep their internal fires burning. This relationship shapes the ecology of every warm-blooded creature, from mice to elephants.[2]

Modern research using infrared thermography has even shown that this system is responsive to our emotions. Stress or fear can trigger immediate vasoconstriction in the nose or extremities, a visible thermal shift that reveals the deep connection between our physiological state and our internal climate control.[6]

Sources

- Interdependent Preoptic Osmoregulatory and Thermoregulatory Mechanisms Influencing Body Fluid Balance and Heat Defense

- Body Size and Temperature: Why They Matter

- Homeostatic Processes for Thermoregulation

- Regulation of Brown Adipose Tissue Activity by Interoceptive CNS Pathways

- Physiological and Behavioral Mechanisms of Thermoregulation in Mammals